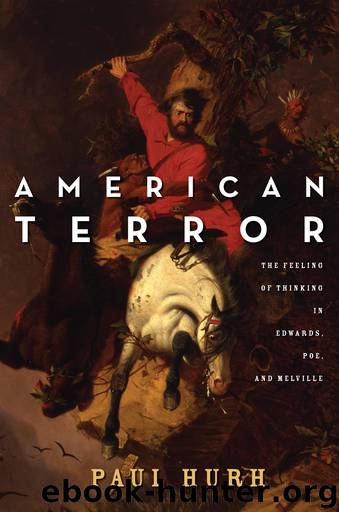

American Terror by Hurh Paul

Author:Hurh, Paul [Hurh, Paul]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Stanford University Press

Published: 2015-04-14T16:00:00+00:00

4

THE UNEVEN BALANCE

Dialectical Terror in Moby-Dick

IF YOU WOKE UP to find yourself a character in a Melville fiction, chances are you would be afraid. Your fears might be rational: you might be afraid that you had fallen in with cannibals who have culinary designs upon your flesh (Typee) or that a vengeful slave will slit your throat with the razor he brandishes at your neck (“Benito Cereno”). Your fears might be superstitious: you might find yourself horrified to discover that you have to sleep in the bunk recently vacated by a frenzied suicide (Redburn) or wonder at the ghostly grip of an incorporeal hand upon your own (Moby-Dick). Or your fears might be abstract: you might be terrified by the slow, meaningful crawl of tortoises (“The Encantadas”) or ponder the unidentifiable anxiety provoked by the simple but stubborn preference of an underling (“Bartleby”). The diverse fears in Melville’s fiction share one trait: they are almost always touched with epistemological ambiguity. It isn’t that you have been captured by cannibals, but that you can’t be sure whether or not you have been captured by cannibals. It isn’t that you are holding hands with a ghost, but that you’re puzzled long afterwards, “to this very hour,” by what that horror means. And the most fearsome element in Melville’s work, the whale, frightens not by being dangerous and toothy but by being white. Why hue rather than incisor? Because the ambiguity of whiteness cuts a deeper wound. “[B]y its indefiniteness,” Melville supposes, “it shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe” (MD 195).

Ambiguity invites interpretation. Critical appraisals find in the catalogue of fears indices of the racial, legal, and economic pressures of the historical period, psychosexual patterns of biographical and national identity, and philosophical arguments about the nature of freedom or the existence of God. What you find in Melville’s fears depends upon your approach, and few American authors offer so many possible approaches. On one hand, Melville’s metaphysical search for foundational truth and authority appeals to philosophical critics looking past the ephemera of history to the “big questions” of personhood, ethics, and epistemology. On the other hand, the complex wealth of cross-cultural influence upon his work appeals to historicist critics looking to restore the context of the political and cultural issues of Melville’s day. Half head and half hands, the balance between the abstract philosophy of an ahistorical order and the real conditions of antebellum America secures Melville’s work as opportune to the present literary critical moment that is itself pulled between roughly philosophical and roughly historicist ends.

But in both varieties of interpretation, Melville’s thematic fears are usually read as dispositional symptoms, thus allowing commentary to move quickly past the specific fear to the case of its arguable cause. This isn’t so much a mistake as it is an expediency, for to attend to the textures of those fears individually, to ponder over the unique problem that fear presents to his narratives, is to begin to sense that our usual

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African | Asian |

| Australian & Oceanian | Canadian |

| Caribbean & Latin American | European |

| Jewish | Middle Eastern |

| Russian | United States |

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12359)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7737)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7308)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5745)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(5731)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5400)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5067)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4923)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4711)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4557)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4539)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4505)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(4430)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4084)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4013)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(3997)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(3981)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3964)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3831)